Medieval Weapons

Medieval weapons were used for various reasons, including warfare, self-defense, hunting, and sport. Different types of weapons were used for different types of fighting. And then there were the medieval siege weapons for overcoming castle defenses.

Let's explore them all.

Battering Ram

A siege engine designed to break open stone walls or splinter wooden doors or gates. The first battering rams were nothing more than a heavy log carried by several people and propelled with force against a door. Later, battering rams encased the log in a fire-resistant, arrow-proof canopy on wheels. The log was suspended on chains or ropes to improve the force of the swing. A capped ram would have the log covered in iron or steel at the end that strikes the wall or door. The canopy on most rams would be curved or slanted like a roof with side screens to protect the workers of the ram from arrow or spear volleys from above.

Defenders inside castles tried to counter battering rams by dropping obstacles in front of the ram, such as bags of sawdust, to keep the ram from getting to the door. Alternatively, they would drop heavy boulders on the ram from the battlements or pour hot oils on the ram and set it on fire. However, the fire method could backfire by catching the door on fire if the ram managed to break through.

Siege Tower / Belfry

A siege engine constructed to protect attackers and ladders while approaching the walls of a castle. Often shaped like a tower, they were as high as the castle walls or more and had wheels. They were usually made of wood and thus flammable and susceptible to attacks with Greek fire, so they were often covered in animal skin or iron to reduce the fire risk.

Siege Towers were used to overcome a castle's defenses by getting troops over the castle walls. They would contain pikemen and swordsmen, and when rolled next to a castle wall, a gangplank would be dropped, creating a walking platform onto the castle battlements. They also enabled archers to stand on top of the tower and launch arrows at the soldiers on the battlements.

At the Siege of Kenilworth Castle in 1266, 200 archers and 11 catapults operated from a single siege tower, though it did little to hasten the castle to surrender as the siege lasted almost a year.

Catapult

Ballistic siege weapons used to launch projectiles a great distance without the use of gunpowder. They use the sudden release of stored energy to propel their projectile. Catapults were used to damage castle walls or gates by launching large rounded stones at them, but they also could toss garbage or carcasses over the walls to spread disease and try to get the people inside the castle to surrender. Below are the most common types of catapults used in the Middle Ages.

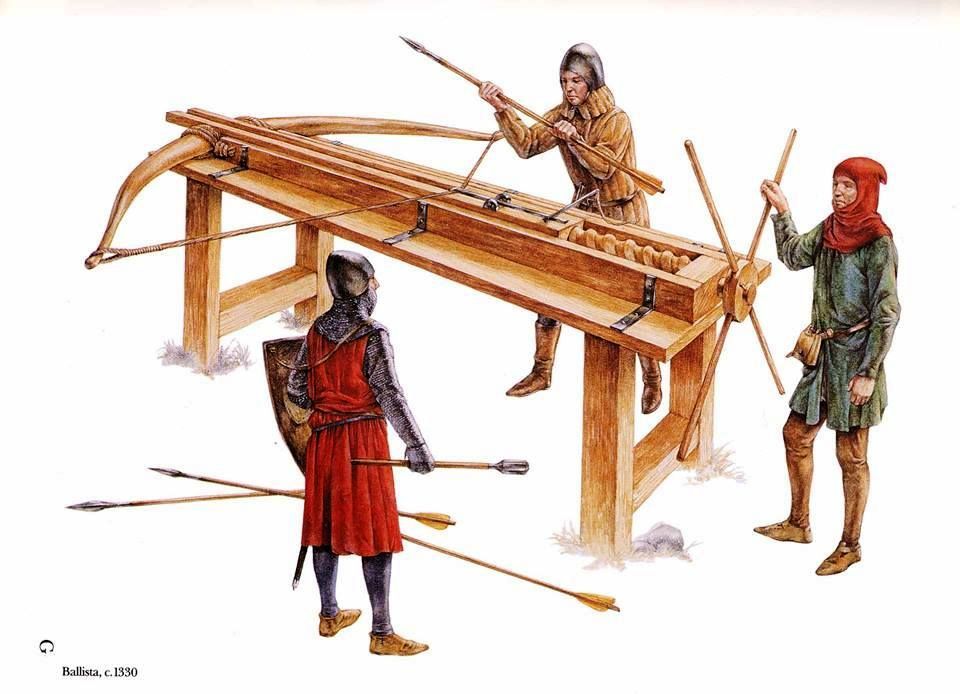

Ballista / Scorpio

A ballista was a catapult weapon that launched large bolts, darts, and stones at a distant target. It used two levers with twisted springs instead of a tension prod to build torque and firing energy.

These weapons were popular in Roman times, but with the decline of the Roman Empire, resources to build and maintain them became scarce, and the onager and springald gradually replaced the Ballista. Despite its decline, it was still a useful weapon in siege warfare until the arrival of the canon.

Several Ballistas are recorded being held under the English Crown: four balistas at Duluithelan Castle in 1280, one balistam de tur at Rothelano Castle, and one magnam ballistam at Bere Blada Castle in 1286.

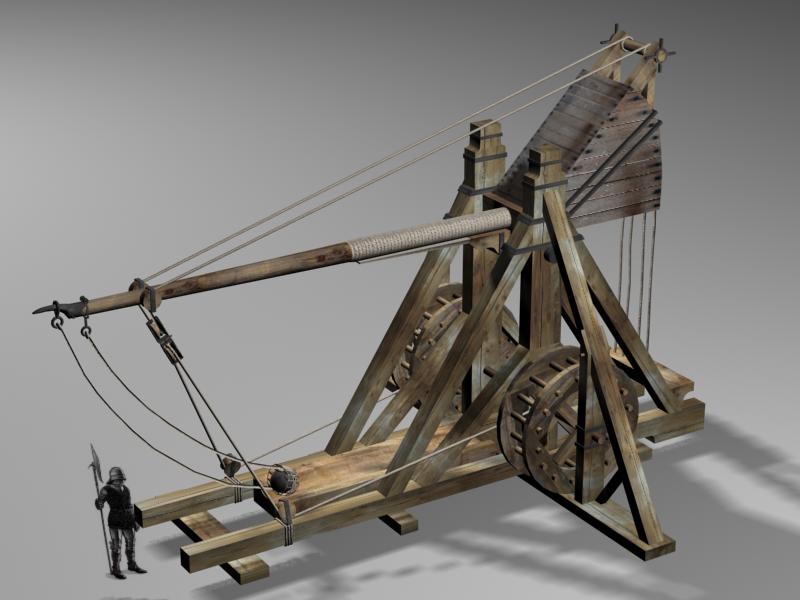

Mangonel

A mangonel was a type of trebuchet, but unlike the counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel was operated by men pulling cords attached to a level and sling to generate the force to launch projectiles.

It required more men to operate than a counterweight trebuchet but was faster to reload than the onager it replaced in early Medieval Europe. The counterweight trebuchet replaced the mangonel in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The mangonel was used as an anti-personnel weapon alongside archers. Mangonels were still used as late as the siege of Acre in 1291. The Mamluk Sultanate fielded 70-90 trebuchets, mostly mangonels with about 15 counterweight trebuchets. The Templar of Tyre described the faster-firing mangonels as more dangerous to the defenders than the counterweight trebuchets.

Onager

A torsion-powered siege engine with a bowl, bucket, or sling at the end of its throwing arm. The onager had a large wooden frame placed horizontally to the ground with a vertical frame of solid timber fixed to its front. A vertical arm that passed through a rope bundle fastened to the frame had a cup affixed to the end to contain the projectile.

To fire the weapon, the arm was forced down against the twisted ropes by a windlass and suddenly released. As the arm swung, the projectile would be hurled forward. The arm would be caught by a padded beam fixed to the vertical frame, ready to be pulled down for the next shot. An onager took eight men to wind down the arm. The recoil of the arm was so significant that an onager could not be placed on castle walls as the stones would become dislodged.

Springald / Espringal

A medieval torsion artillery device for throwing bolts from the late 12th century. It is constructed on the same principles as a ballista, but with inward swinging arms in a skein of twisted sinew or hair and threw only bolts. It was housed in a box-like wooden structure and could throw bolts about 180 meters.

The earliest mention of a springald appears in France in 1249 and is first attested to as part of the arsenal at Reims in 1258. Springalds were often used to defend castle gates from the top of towers. By 1382, the springald was being phased out in favor of crossbows and firearms.

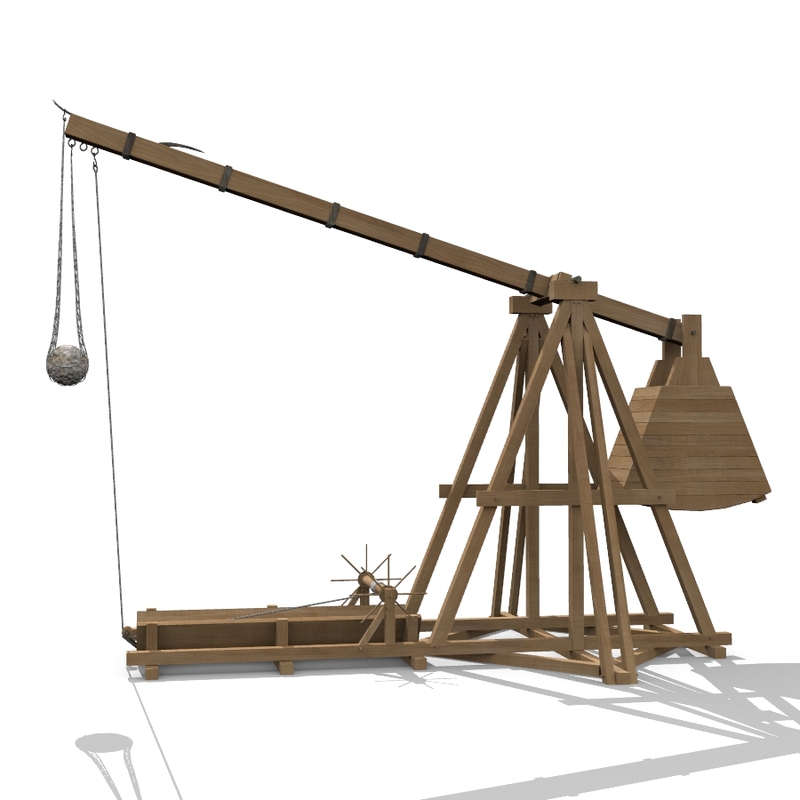

Trebuchet (Counterweight)

The most potent catapult siege weapon in the Middle Ages was the trebuchet. It uses an extended arm as much as 50 feet long to launch large projectiles farther than other catapults. The counterweight trebuchet uses a counterweight to swing the arm using gravity. Energy is stored by slowly raising a heavy box filled with stones and sand attached to the short end of the beam. A sling attached to the other end of the arm holds the projectile. When the heavy box is released, gravity drops the box, forcing the arm to swing and launch the missile. Once the missile is fired, the arm continues to rotate, slow on its own accord, and come to rest, unlike other catapult designs where the frame absorbs most of the launching energy.

The projectile could be anything, debris or rotting carcasses, but typically, a large stone worked until round and smooth, giving it the best range and predictability for hitting a castle wall. Sometimes, the projectile would be covered in Greek fire just before launch, turning it into a fireball and inflicting more damage on anything flammable it may have hit when it reached the castle.

The most famous account of a trebuchet was in 1304 at the Siege of Stirling Castle, when Edward I (Longshanks) attacked the castle during the Wars of Scottish Independence. It was called the War Wolf, or Loup-de-Guerre, and was the largest trebuchet ever built. It took 30 wagons to transport it when disassembled. It then took carpenters three months to assemble the trebuchet once in range of Stirling Castle. The Scots inside the castle tried to surrender to Edward, but he refused their surrender until after the trebuchet was built and fired at the castle. The War Wolf fired a single stone through two of the castle's walls “like an arrow flying through cloth.” Afterwards, Edward accepted the surrender of Stirling Castle.

Battle Axe

An axe specifically designed for warfare. They weighed between 1 and 7 pounds and were 1 to 5 feet long. Axes were cheaper than swords and more plentiful in the Middle Ages, particularly during the Viking Age. They were designed to cut through arms and legs rather than wood, so the battle axe blade was lighter and thinner than a standard axe, making it quicker to bring to bear in combat.

They are featured in the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts Norman knights against Anglo-Saxon foot soldiers during the Battle of Hastings. Robert the Bruce used a battle axe to defeat Henry de Bohn in single combat at the start of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

Bludgeon / Club / Cudgel

A short stick or staff, usually made of wood, wielded as a weapon to create blunt force trauma on an enemy. The club was the most straightforward and cheapest weapon, dating from prehistoric times. Most clubs were small enough to be wielded with one hand. A cudgel was a stout stick used by peasants in the Middle Ages. It was used as a walking stick but also a weapon in wartime.

Flail

A melee weapon consisting of a wooden staff with a striking head affixed to the staff by a length of chain or rope. The chain enabled the weapon to strike around a defender's shield. However, it came with a lack of precision when attacking and was challenging to use in close combat.

A peasant flail was a two-handed weapon with a long shaft, sometimes improvised from farming equipment by peasants conscripted into the army or caught up in a local uprising. Such modified flails were used in the German Peasants' War in the 16th century.

A military flail was shorter, with one or more chains attached to the end with metal balls of spikes. Military flails are popular in fictional works such as films or role-playing games but were rare weapons in combat and never saw widespread use. One reason was that if the flial were swung at an enemy and missed, the momentum of the swing and chain would continue, causing extra time before the weapon could be ready for another swing, making the user more susceptible to a counterattack.

Mace / Pernach

A blunt club or rod for delivering blows in hand-to-hand combat, made of metal or wood reinforced with metal, and has a head of stone, bone, or metal. Maces used by foot soldiers were two to three feet long. The mace of a cavalryman was longer to enable use from horseback.

The head of the mace is often shaped with flanges or knobs to help break through plate armor. The use of flanges on a mace became popular in the 12th century. The pernach was a type of mace used throughout Europe. Its name comes from the Slavic word pero, meaning feather. The flanges on a pernach mace resembled a fletched arrow and could penetrate chain mail and plate armor.

Ceremonial maces, still used today, are richly decorated and usually contain a coat of arms or other symbols. They are displayed as a symbol of jurisdiction and authority.

Morning Star

A club-like weapon consisting of a shaft with a ball adorned with spikes at one end, resembling a mace. These were hand-to-hand combat weapons used to inflict blunt force and punctures to injure or kill the enemy.

The morning star was used at the beginning of the 14th century. The spikes distinguish it from a mace, which has flanges. Morning stars had shafts made of wood and were longer than a mace, often used as a two-handed weapon.

Morning stars are often confused with the flail, a wooden shaft with a chain length at the end and a ball of spikes attached to the chain. On a morning star, the ball of spikes is attached to the end of the shaft.

Bow and Arrow / Shortbow

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system used to kill from a distance. A bow consisted of a semi-rigid but elastic piece of wood in an arc shape with a bowstring joining the ends of the bow. An arrow consisted of a long-shafted projectile with a pointed tip at one end and fletching towards the back of the other end with a narrow notch on the very end where the bowstring on the bow would connect with the arrow.

The person shooting the bow and arrow was called a bowman or archer. The person who made arrows was called a fletcher, and the person who made the metal arrowheads was called an arrowsmith. To shoot, an archer holds the bow at its center with one hand and pulls back the arrow and the bowstring with the other, building elastic energy. Once the bowstring is released, the arrow propels forward.

The shortbow had a range of about 100 yards and could kill and could kill or injure an unarmored man at close range, but it was less useful against armor. At the Battle of Hastings, both sides used the shortbow, but the Norman archers had more success as they fired their arrows into the air onto the enemy from a high arch, which bypassed shields. It is said that King Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings by an arrow through the eye.

Crossbow / Arbalest / Stone Bow

A ranged weapon used to shoot arrow-like projectiles called bolts or quarrels. The crossbow uses an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a prod, which is mounted horizontally on a frame called a tiller. It is a hand-held weapon similar to the stock of a rifle. The crossbow locking mechanism maintains the draw until the weapon is ready to fire by pulling the trigger or depressing a lever.

The crossbow replaced hand-drawn bows in Europe during the 12th century, except in England, where the longbow remained popular.

The arbalest was a variation of the crossbow in the 12th century with a steel prod. It was larger than the crossbow and had a more significant force since it was made of steel. But it also had a shorter draw length, limiting the energy it could transfer to the arrow bolt when firing.

A stone bow is a modified crossbow version that fires stones or bullets as projectiles instead of bolts. Stone bows were used primarily for hunting.

Longbow

The longbow is a tall bow, usually 5 to 6 feet long, that makes a long draw possible. It is generally made of yew for its elasticity and is relatively narrow, with the bow's limbs curved or D-shaped. It was made of a single piece of wood, making it quick and easy to craft. They were famous for their long range and accuracy. During the reign of Edward III, it was suggested that an arrow fired from a longbow could reach a distance of 400 yards.

Longbows were legendary in the Middle Ages, used in great numbers against the French in the Hundred Years' War at the battles of Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt. Their dominance continued until the battles of Formigny and Castillon, when the French began to use cannons to break the lines of English archers.

In England, the use of the longbow continued in the Wars of the Roses and well beyond the use of firearms. The last battle on English soil, where the longbow was used as the primary range weapon, was at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. The Battle of Tippermuir in 1644 in Scotland may have been the last battle to involve the longbow in significant numbers.

Arming Sword / Knightly Sword

A typical sword from the High Middle Ages of the 10th to 13th centuries. It was usually about 30 inches long with a straight double-edged blade. Its distinct characteristic is its cross-shaped crossguard above the hilt.

The term arming sword was first used in the 15th century to refer to this single-handed type of sword after it had ceased to serve as the main weapon and began to be used as a sidearm. It was typically used with a buckler or shield.

It was common for arming swords to have engravings on the blade in the 12th century, often inspired by religious formulae, especially the phrase “in nomine domini” and the word “benedictus”.

Claymore / Great Sword

A large two-handed double-edged sword used in Scotland in the late Medieval and early modern periods. The Claymore was set with a wheel pommel often capped by a crescent-shaped nut and a guard with straight, forward-sloping arms that ended in quatrefoils. The average Claymore was about 55 inches long with a 13-inch grip and weighed over 5 1/2 pounds.

The Claymore was used in clan warfare and border fights with the English from 1400 to 1700. Smaller claymores date back to the Wars of Scottish Independence. The Claymore was an offshoot of the longsword.

The English had a similar but smaller sword to the Claymore called the Great Sword.

Dagger / Dirk

A double-edged fighting knife with a very sharp point. The dagger was a thrusting or stabbing weapon used in close hand-to-hand combat. Most daggers also have a cross guard to protect the hands from moving forward onto the sharpened blade.

Though around since antiquity, the dagger reappeared in the 12th century as the knightly or quillon dagger and developed into a standard weapon for civilian use or a secondary weapon in close combat. Even when combatants wore full plate armor, the dagger was useful in penetrating between the joints in the armor where other weapons were less effective.

A dirk is a long-bladed thrusting dagger made famous by the Highland dirk. It is used primarily in Scotland as a personal weapon of naval officers and the side weapon of Highland Clansman.

Katana

A Japanese sword with a curved single-edged blade with a circular or square guard and a long grip for use with two hands. The blade was 24 to 30 inches long, and the edge faced upward.

The katana was used by samurai in feudal Japan in close combat and was considered among the finest cutting weapons in military history.

Katana swords were often used as gifts between feudal lords or as offerings to the kami enshrined in Shinto shrines as symbols of authority and spirituality of samurai.

Longsword / Bastard Sword

It is a double-edged straight-blade sword with a cruciform hilt and a long grip between 6 and 12 inches for two-handed use. The blade was usually between 30 and 45 inches long and weighed around 2 to 3 1/2 pounds.

It is much like the knightly sword, only longer, and was used mainly between 1350 and 1550, with some use into the 17th century. The longsword emerged as a military weapon in the early stages of the Hundred Years' War.

It gained the name bastard sword in the 15th or 16th century as an irregular sword or sword of unknown origin. By the mid-16th century, the name was associated with large swords. The sword is characterized by the long grip, not the blade, indicating it was designed for two-handed use.

Rapier / Espada Ropera

A one-handed sword with a straight, slender, and sharply pointed double-edged blade, popular in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries as a symbol of nobility or gentlemanly status. The hilt was usually complex and designed to protect the whole hand, with later rapiers evolving with a cup-shaped hilt.

Rapier is a Spanish term derived from “ropera,” referring to a sword used with cloths, espada ropera, or dress sword. These swords were good at thrusting but poor at cutting and were popular during fencing, dueling, and sometimes combat.

A large pommel, often decorated, secured the end of the hilt and provided weight to balance the blade.

Ulfberht Swords

A group of about 170 double-edged medieval swords that date from the 9th to 11th centuries, and the blades bear the inscription +VLFBERH+T or +VLFBERHT+. Ulfberht is a Frankish name, possibly indicating where the swords originated, likely in the Rhineland region, the core region of the Frankish realm.

These particular swords were transitional between the Viking and the high medieval knightly swords. They also mark the beginning of blade inscriptions. The reverse side of the sword sometimes had a braid pattern engraved on the blade.

Ulfberht swords averaged around 2.7 pounds in weight and were about 36 inches in length. They were a one-handed sword with a pommel hilt.

Bardiche / Lochaber Axe

A polearm weapon used from the 14th to 17th centuries. The shaft of the bardiche was the shortest of all the polearms, rarely exceeding 5 feet in length. It was similar to the halberd, as it had an axe affixed to the end of the shaft, but the axe was a large, clever-like blade. The bardiche also does not have the spike atop the blade nor the hook on the opposite side of the blade as on the halberd.

With a narrow blade end, the bardiche was helpful as a thrusting weapon and for chopping blows to destroy armor. It was imported to Scotland in the 16th century.

Scotland also had the Lochaber axe, which was similar to the bardiche but had a small hook attached to the back of the blade, a butt spike as a counterweight to the axe, and langets down each side of the shaft to prevent the head containing the axe from being split from the shaft. Hundreds of Lochaber axes were used to arm the Earl of Mar's troops during the Jacobite rising of 1715.

Bec de Corbin

A type of polearm that was popular in medieval Europe. The name is Old French for “raven's beak”. It consists of a long pole with a modified hammerhead and a spike on one end. The hammerhead consisted of a long fluke or beak on one side and a blunt hammer on the opposite side. The beak side was used as the primary part of the weapon for tearing into plate armor or mail.

The spike on the end of a bec de corbin was also shorter than that of a Lucerne hammer. The head was smaller than those found on a halberd, which helped concentrate the kinetic energy of the blow on a smaller area, increasing its ability to defeat armor.

Glaive / War Scythe

A polearm weapon consists of a wooden staff about 2 meters long with a single-edged curved blade attached to one end in a socket shaft configuration like an axe. The convex side of the blade is edged. Some have a small hook on the back side of the blade. Foot soldiers used these for unhorsing cavalrymen. Conversely, the glaive was also used on horseback in mounted combat.

The glaive may have originated in Wales. A warrant from the reign of Richard III in 1483 mentions “the making of two hundred Welsh glaives” for twenty shillings and sixpence for thirty glaives with their staves, made at Abergavenny and Llanllowel.

A war scythe is similar to the glaive, except the edge of the blade is on the concave side of the blade.

Halberd / Swiss Voulge

A two-handed polearm that was predominant from the 13th to 16th centuries consisted of a 5 to 6-foot-long wooden shaft topped with an axe blade and a spike. The halberd also sometimes included a hook on the opposite side of the axe blade. It worked in much the same way as the bec de corbin or the Lucerne hammer, with the spike being used as a thrusting weapon and the hook to pull knights off of their horses, but the axe, instead of a hammer, made it more of a cleaving weapon that could cut through weaknesses in armor.

The halberd was first mentioned in the 13th century and was also described as a new weapon by German poet John of Winterthur used by the Swiss at the Battle of Morgarten in 1315.

Most famously, it was a halberd that pierced the skull of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. Halberds remain the ceremonial weapon of the Swiss Guard in the Vatican and the Alabarderos Company of the Spanish Royal Guard.

Horseman's Pick / War Hammer

A War Hammer consists of a handle and a head. The length of the handle varied between 2-3 feet and 5-6 feet, with the longer handled hammers being used by standing soldiers and short ones used on horseback.

War Hammers were a popular weapon in the late medieval period, as swords and axes could no longer pierce armour. The hammers could transmit their impact through helmets and cause concussions. The spike end could be used for grappling armour, reins, or an enemy's shield.

Lance

A long thrusting spear used by a mounted knight or cavalry soldier. It was not suitable for throwing or repeated thrusts like the pike. Lances were equipped with a vamplate, or small circular plate, that prevented the hand from sliding up the lance upon impact and protected the hand. Knights would also carry a sword, mace, or axe and the lance for hand-to-hand combat.

Nothing was more terrifying in a pitched battle than a wall of knights on horseback charging in formation at full speed with lances in an underarm-couch position, which would decimate any infantry line of defense.

A jousting lance was a variation used in jousting contests, not warfare. The jousting lance had a blunted end and was usually hollow so that it would break on impact. The goal of the joust was to hit your opponent and, at worst, unhorse them, but not to hurt them, though accidents happened.

Lucerne Hammer

This type of polearm was popular in Switzerland in the 15th and 17th centuries. It comprised a 6 to 7-foot-long wooden shaft with a 3 to 4-pronged hammer head mounted on one end with a spike on the reverse side of the hammer and an even more prolonged spike on top of the hammer, a combination of a bec de corbin and a war hammer.

The Lucerne hammer was a two-handed polearm and had multiple functions in fighting. The spike on the end was used in thrusting attacks, while the hammer was used to create blunt force injuries or to break armor. The spike on the reverse side of the hammer was used to pull men from their horses.

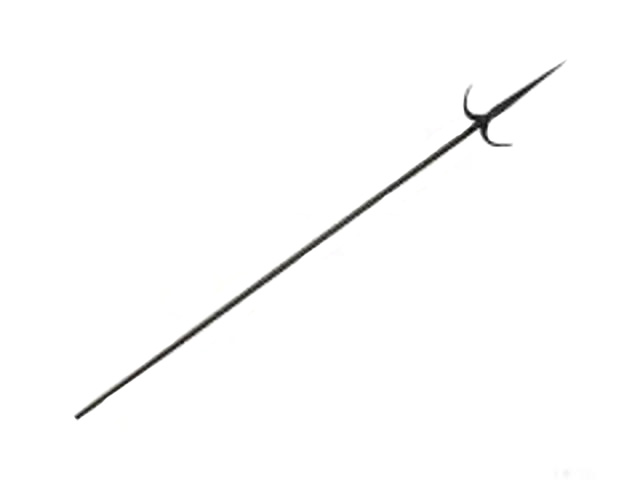

Partisan / Ranseur

A type of polearm in Europe during the 16th to 18th centuries consisting of a long wooden shaft with a spearhead mounted on one end. The spearhead had protrusions on each side, which aided in blocking sword thrusts. Foot soldiers primarily used the partisan to defend against cavalry charges.

With the arrival of gunpowder and firearms, the partisan was removed from the battlefield as a useful weapon. However, it was still used as a ceremonial weapon for guards at important buildings or events.

The ranseur was similar to the partisan in design, with the protrusions on the side of the spearhead being crescent-shaped and generally not edged for cutting. These were more useful for pulling mounted soldiers from their horses.

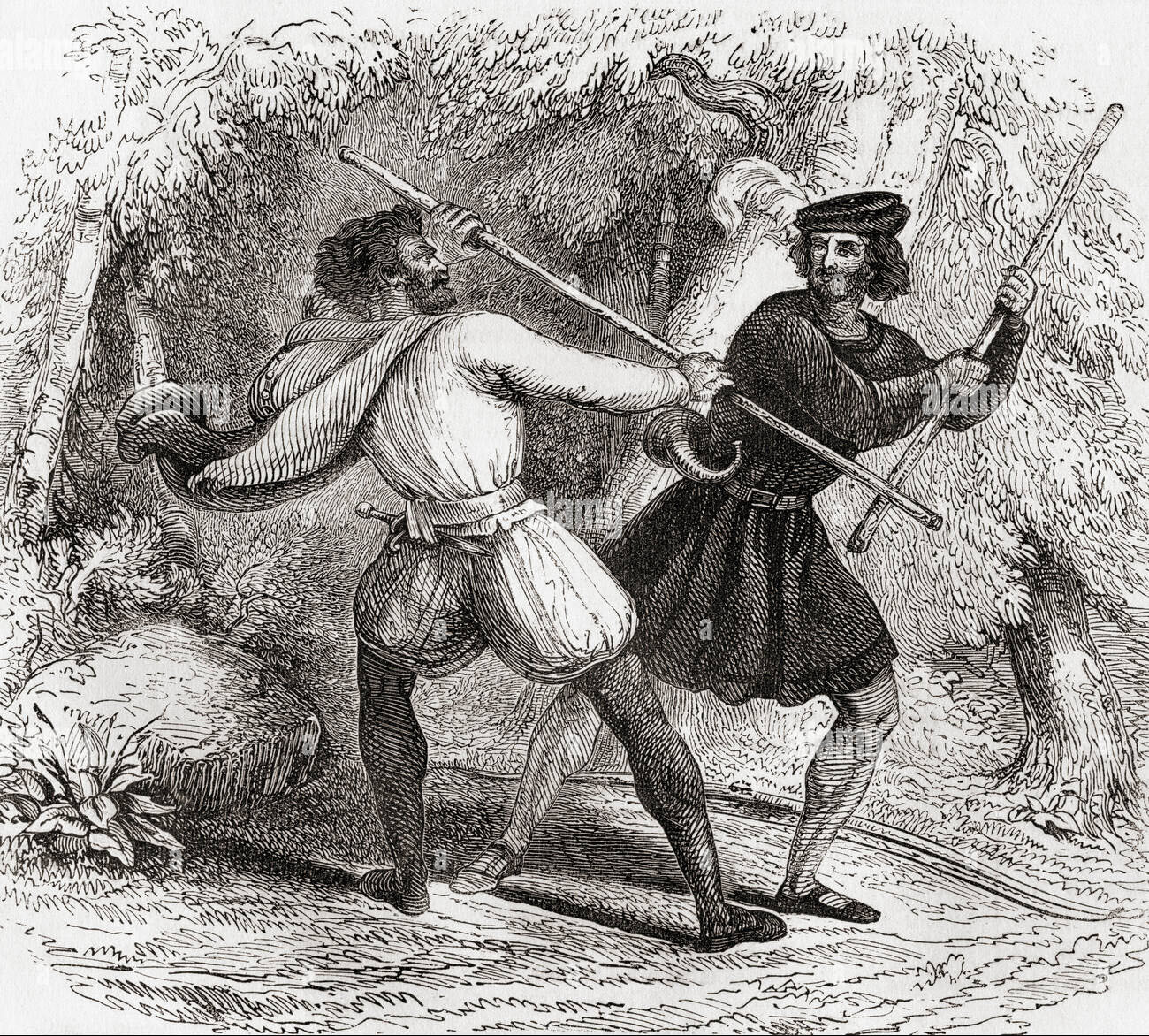

Quarterstaff / Short Staff / Long Staff

A polearm weapon that was popular in England in the late Middle Ages, sometimes referred to as a national English weapon, The quarterstaff, or short staff, was a shaft of hardwood, usually 6 to 9 feet long, sometimes with a metal tip or spike at one or both ends. A long staff was between 11 and 12 feet in length. The term quarterstaff possibly comes from how the staff was held, with the right hand grasping it one-quarter of the distance from the end.

Blows with a quarterstaff were often delivered downwards, but sometimes blows to the legs were done. Thrusts were also performed with the release of the forward hand and a step with the forward leg, much like a fencing lunge.

Spear / Pike

A pole weapon consisting of a long shaft of wood, usually 6 to 8 feet long with a pointed head. The shaft could be carved to a point on the end to form the head, or the head could be made of a more robust material like iron or bone. There are two categories of spears: one designed for throwing, such as javelins, and one used in hand-to-hand combat for thrusting, such as lances or pikes. The pike was a spear, only longer, usually between 9 to 23 feet long.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, spears continued to be used in the Middle Ages as they were cheap and easy to make. Spears were useful at thrust attacks against an enemy but even more effective as a defensive mechanism against knights on horseback.

Spears were best used in tight formations such as a shield wall or a schiltron. Robert the Bruce used a rectangular schiltron formation at the Battles of Bannockburn and Old Byland to repel the English Calvary. Spears fell out of use in the 14th century when the halberd became popular. What spears did exist evolved into the longer pike and were still used by foot soldiers well into the 17th century.

Spetum

A 13th century polearm weapon consisting of a 6-8 foot long staff with a spearhead mounted on one end and two single-edged projections at the base of the spearhead set at acute angles. The spearhead blade was about a foot long, and the slide projections were half that length. The spetum was a thrusting weapon used in hand-to-hand combat. The projections were used to bind weapons and could also be used to knock shields to the side. The single edge on the projections gave the spetum more strength to the sharpened side than is possible with a dual-edged construction.

The spetum was used by foot soldiers. The design allowed them to engage with multiple enemies simultaneously, provided an increased reach, and helped exploit gaps in plate armor.

Arquebus / Musket

A form of long gun dating from the 15th century, it was used in Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Arquebus and musket are both types of early firearms that were used in warfare. Initially, arquebus referred to a handgun with a hook-like projection or lug useful for steading the gun against castle battlements when firing. Adding a shoulder stock, priming pan, and matchlock mechanism turned the arquebus into the first handheld firearm with a trigger. A standard arquebus called the caliver was introduced in the late 16th century. The matchlock arquebus was considered the forerunner to the flintlock musket.

Arquebuses played a decisive role in the Battle of Cerignola in 1503, the first recorded use of the arquebus in military conflict.

The musket, a large arquebus, was introduced in 1521 but fell out of favor due to the decline of plate armor. The term musket remained and became a general term for smoothbore gunpowder weapons.

Blunderbuss

A 17th to 19th century firearm with a short, large caliber barrel, commonly flared at the muzzle. The blunderbuss is considered the predecessor to the modern shotgun. A handgun version of the blunderbuss was called a dragon, from which the term dragoon evolved.

The flared muzzle is the critical feature of the blunderbuss, which was not only meant to make loading shot quicker and easier, but when fired, the muzzle allowed the shot to spread into a wider field of target.

Blunderbusses were usually only 2 feet long and effective at short range, as they needed more accuracy at long distances. The blunderbuss and, even more so, the dragon were primarily used by cavalry troops who needed a lightweight firearm. They became so synonymous with the cavalry that the term dragoon was used to refer to mounted infantry. Outside of war, the blunderbuss was used to defend mail coaches and also used by pirates.

By the middle of the 19th century, the blunderbuss was phased out and replaced by the carbine in military conflict.

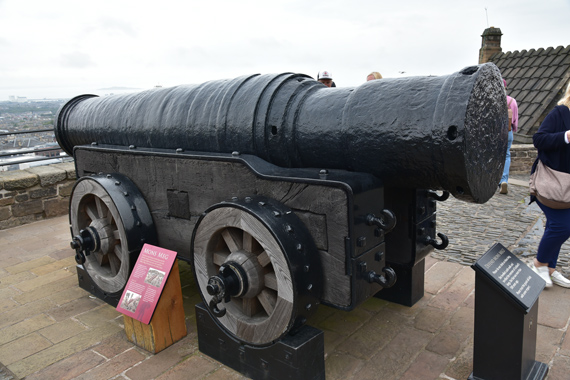

Bombard / Cannon

A type of cannon used throughout the Middle Ages. Bombards were large-caliber muzzle-loaded artillery used to fire large round stones at castle walls during sieges. Most were made of iron and used gunpowder to launch the projectiles.

The term bombard was initially used to describe guns from the 14th century but later applied to only large cannons.

England began using bombards in the 14th century, which King Edward III used at the Battle of Crécy in 1346. Henry V captured Harfleur with bombards in 1415. Henry and his army would later come under artillery fire at the Battle of Agincourt. King James II of Scotland destroyed many castles with his 1 ½ ton bombard named “The Lion.” King James II also used Mons Meg, the largest bombard of its time, built around 1449, which was also used to destroy castle walls. It can be found today at Edinburgh Castle. James II was very fond of cannons, and they would be his undoing when, while besieging Roxburgh Castle in 1460, the cannon he was standing next to exploded and was killed in the explosion.

Some castles, such as Bodiam Castle and Cooling Castle, have inverted keyhole gun loops in the castle walls for firing small cannons from the castle towards attackers.

Mortar

A lightweight muzzle-loaded weapon consisting of a smooth-bore metal tube affixed to a base plate used to launch large projectiles in a high-arching trajectory.

From the 17th century, siege mortars were made of iron with an outside diameter many times the bore diameter. A “Roaring Meg” mortar with a 15.5-inch barrel diameter was the largest mortar used during the English Civil War in 1646. It fired a 220-pound hollow ball filled with gunpowder.

Roaring Meg was used by Parliamentarian forces in the siege against Goodrich Castle. Following its success at Goodrich Castle, it was taken to assist in the bombardment of Raglan Castle. Roaring Meg has been preserved and displayed at Goodrich Castle since 2004.

Organ Gun / Ribauldequin

A late medieval volley gun with multiple iron barrels aligned parallel to each other on a platform. When fired, all barrels would fire simultaneously, causing a much higher rate of damage to the enemy. They were lighter and more mobile than other artillery then and were primarily used against enemy personnel rather than attacking a castle. Organ guns were used between the 14th and 17th centuries.

The first known organ gun used in battle was in 1339 when Edward III's army used them in France during the Hundred Years' War. These had twelve barrels, thus firing twelve iron balls at a time. Ribauldequins were also used during the Wars of the Roses when Burgundian soldiers under Yorkist control used them at the Second Battle of St Albans.

Caltrop / Crow's Foot

A caltrop is an area denial weapon. The Romans called them “tribulus,” derived from the Greek word “tribolos”, meaning three spikes. A caltrop has two or more sharp nails or spikes up to three inches long, arranged so one spike always points upwards from a stable base.

Caltrops were used by spreading them on the ground to slow advancing troops, especially horses, as they would be stepped on and cause damage to the soft tissue under the foot.

Caltrops can also be used in various symbolic ways and as a charge in heraldry. The Finnish noble family has three caltrops argent in their coat of arms. The caltrop is also the shoulder insignia for the U.S. Marine Corps’ 3rd Division.

Greek Fire

The term “Greek fire” has been used since the Crusades, but before that, it was referred to as sea fire, Roman fire, war fire, or liquid fire. Greek fire was an incendiary liquid added to arrows or siege weapon projectiles. It was set on fire and launched to inflict more significant damage on castles, especially if the missile hit something flammable.

How to make Greek fire was a closely guarded secret. So much so that the formula is now lost to time; it is said that this liquid substance was a combination of pine resin, quicklime, and other substances and was resistant to water. In fact, pouring water on the Greek fire made the fire spread even more. It could only be extinguished by a few substances like sand or strong vinegar.