Anatomy of a Castle

Medieval castles were built for defense. Almost all parts of a castle serve a defensive purpose and help create multiple layers of protection. Nothing was made by chance. When visiting a castle, consider why this wall or tower was built where it stands or how it used the landscape as part of its defenses.

Sometimes, a castle not only uses the landscape, like a river, as a natural moat but may have also been built in that location to protect that landscape, like a strategic river crossing, or to serve as a toll location for river traffic, like the Robber Knights on the River Rhine in Germany. Sometimes, faith was a factor in a castle's layout.

Let's break down the different parts of a castle.

Drawbridge / Turning Bridge

A movable bridge at the entrance to a castle or tower surrounded by a moat or ditch. Drawbridges provide access across a moat or ditch but can quickly be raised from within the castle to deny entry to an enemy.

Typically, a drawbridge would be located immediately outside a gatehouse or barbican, consisting of a wooden deck with one edge hinged against the gatehouse threshold, so when raised, the bridge would be flush against the castle gate, providing an extra barrier for entry. This also made the moat or ditch more challenging to cross. More defenses would be behind the drawbridge in the gatehouse, including a portcullis and machicolations above the gate to drop stones or hot water on attackers. Arrow slits in gatehouse towers also provided a means of protection for the drawbridge and entrance.

Drawbridges were raised and lowered using a chain and pulley system, which took a little while to raise or lower, much like the mechanics of a portcullis.

Some castles had what's known as a turning bridge, which pivoted up and down. The end closest to the castle carried counterweights. The turning bridge hung on central trunnions, and the end closest to the castle would not be hinged to the gatehouse but swung downwards into a pit in the gate passage, allowing the bridge to be raised much quicker than a chain and pulley system, like the mechanics of Tower Bridge in London.

Earthwork Enclosure / Dry Moat

Excavated ditches forming a ring around the castle. The excavated dirt created hills on either side of the ditch. The earthworks were essential features of a ringwork-style castle, which used the hills and ditches as part of their defense. Earthworks often had a wooden palisade wall along the top of the ditch. Some castles had multiple concentric earthwork rings surrounding them.

Enemies attacking a ringwork castle would have to navigate down the slope of an earthwork and back up the other side, exposing them to defenders in the castle who had the higher ground, especially archers. Attackers would wear chainmail or armor, which protected them but also slowed them down as the earthwork slopes were more difficult to climb with the added weight of the armor. Having climbed the ditch, they could then be met by defenders standing outside the castle wall on a flat area between the wall and the slope of the trench, known as a berm.

Moat

A deep, broad ditch surrounding a castle, providing a preliminary line of defense. Moats can either be dry or water-filled. Water-filled moats offer extra protection, preventing attackers from moving siege towers or battering rams beside castle walls. Also, a knight in armor would find it challenging to cross water in the armor. A water-filled moat also prevented attackers from tunneling underneath a castle to cause walls or towers to collapse.

Moats were dug around a castle and then filled with water. Some castles, like Bodiam Castle, filled the moat by redirecting a nearby stream or river. Today, moats provide castles with a romantic setting with reflections of the castle on the water, which is just an aesthetic bonus to their original defensive purpose.

Roman Walls

When the Romans occupied England in the 1st century BC, they built defensive forts at crucial locations to control the countryside. Some 500 years later, the Roman Empire was overextended and under pressure from new threats back home, so they left England, and the Dark Ages began.

They also left behind stone walls, such as Hadrian's Wall in the North of England, and stone fortifications, mainly along the southern coast. When William invaded England in 1066 and landed at Pevensey Bay, his first action was to build a wooden motte and bailey castle. He placed the castle inside the Roman walls they left behind at Pevensey. This provided William's wooden castle with an instant stone wall perimeter, making defending it easier.

This became a common practice: placing medieval castles within Roman stone fortifications or building castles directly on the Roman wall foundations. Some English cities were encircled with a Roman stone wall, which still exist at York and Chester.

Arrow Loop / Arrow Slit / Rayere

A narrow vertical slit in a castle wall or tower from which an archer can launch arrows or bolts from a crossbow at attackers. The slit was thin, making it near impossible for attackers on the outside to hit an archer behind the wall as they would have to get their arrows to go through the slit. But an archer behind the arrow loop was provided a wider range of fire at the enemy and was also protected by the castle wall. Some arrow slips were cross-shaped, which gave the defender a better horizontal field of vision through the loop.

The one weakness of an arrow loop, particularly behind a thick castle wall, is that it would have to be thinner behind an arrow loop so an archer could be close enough to the loop to shoot through it. So, a castle wall that was typically nine feet thick would be less than a foot wide directly behind the arrow loop. To reduce this vulnerability, the opening behind the arrow loop was the narrowest closest to the wall. Still, it opened into a triangular space, so the wall thickness gradually increased on each side. This triangular space behind an arrow loop is called an embrasure. These gave the archer more room to stand and shoot at angles through the arrow loop, also increasing their target range horizontally. The wider the embrasure, the wider the target range. Arrow loops also sometimes widened at the bottom into a triangular shape, called a fishtail, which provided the archer a clear view of the base of the wall he was defending.

Sometimes long, narrow slits were made in thick castle walls to let light into the castle. This thin slit in the wall is known as a rayere.

Barbican / Gatehouse

A gatehouse is a castle's fortified gateway to control the entrance or entry point. The entrance to a castle was usually the structurally weakest point in a castle wall and the most probable attack point, so they were fortified with the extra defenses of a gatehouse to compensate. Gatehouses would include the portcullis gate, murder holes in the ceiling, arrow loops, and often fronted with the drawbridge. Gatehouses would also often be in the form of a tower and would include rooms on the upper floors for lodging for the guards.

Often confused with the gatehouse is the barbican. The barbican was a thin, enclosed passageway that extended out in front of a gatehouse. The enclosed passageway funneled attackers through a series of dangers, like a portcullis gate, arrow loops, etc., only to have a second set of similar defenses to overcome when they reached the gatehouse. The portcullis gates could be lowered in the gatehouse and barbican, trapping attackers in the passageway as easy targets for defenders.

Some castles only had a gatehouse, whereas the most formidable had a gatehouse and barbican, like the mighty barbican and gatehouse at Warwick Castle in England. The barbican can be seen just over the bridge, with small towers flanking each side of the passageway. The gatehouse is the taller tower behind it, with the clock. It would make an attacker think hard before trying to breach the gate.

Bartizan / Crows Nest / Spur

An overhanging turret projecting from the corners of a castle wall. They provided an additional vantage point to see and defend castle walls under attack. They usually had arrow slits or small windows to fire arrows or cross bolts from while protecting the defender.

Battlements / Parapet Wall / Crenellations

A defensive low wall (chest height to head height) around the top of a castle wall or tower, in which gaps occurred at regular intervals, to allow arrows or other projectiles to be fired while also protecting the defenders behind the wall.

The alternating pattern of walls and gaps enabled a defender to hide behind the raised solid portion of the wall, known as merlons, and then quickly move in front of the gap portion, known as crenels or embrasures (not to be confused with the embrasures behind an arrow loop), to fire arrows at attackers. Sometimes, the merlons would also include arrow loops in the wall so archers would not have to move in front of the crenels to fire at an enemy.

In medieval England and Wales, a “Licence to Crenellate” would be granted by the King, giving the holder permission to fortify their property to the level of a castle.

Bretèche / Brattice

A balcony with machicolations built over a doorway or gate to defend the entrance by shooting or throwing objects at the attackers in front of the door. Bretèches with a roof are classified as closed. Bretèches without a roof are classified as open and are usually accessible from a wall walk or crenel in the battlements. They typically have openings in the floor for dropping stones and sometimes arrow loops.

From the outside of a castle, bretèches look a lot like a garderobe and are similar in construction. However, garderobes are never located above a door or gateway and serve a much different purpose.

Chemin de Ronde / Wall Walk

A patrol pathway along the top of a castle wall, on the inside or bailey side of a wall. These allowed defenders to patrol the tops of the ramparts while being protected by the battlements and provided a means of communication with other parts of the castle.

The wall walk gave defenders an elevated platform to see the enemy and attack using arrows or dropping heavy objects on attackers below the castle walls through machicolations.

Curtain Wall / Rampart Wall

Curtain and rampart walls get interchanged for each other more than most other castle terms. Although similar, there is a difference.

Rampart walls were introduced first and were common in early ring fort castles. The rampart was a length of embankment or wall forming the outer defensive boundary of a castle, usually made of excavated earth from ditches, moats, or masonry. These defined the outer perimeter of a castle in conjunction with the use of an outer ditch and could be enhanced by adding a wooden palisade wall atop the rampart as with motte and bailey castles.

Curtain walls were defensive walls between two fortified towers or bastions of a castle, usually made of stone. These also often formed the same boundary ring around a castle's bailey and replaced the wooden palisade walls atop a rampart. However, with some castles, curtain walls are level with the surrounding area and not placed on an earthen rampart. Curtain walls were often topped with crenelated battlements, a wall walk, or a hoarding. Most curtain walls were thick, allowing for passages built within them and embrasures carved out in front of arrow loops.

In the picture of Warkworth Castle, you can see the earthen rampart wall and the preceding ditch, with the curtain wall between the Carrickfergus Tower and the barbican and gatehouse on top of the rampart wall.

Hourdes / Hoarding

A temporary wooden building-like structure on the top of a castle wall. Used primarily during a siege or attack on a castle in times of war, it gave defenders a wider field of fire along the length of a castle wall, mainly directly downwards at the base of the wall. It also provided protection from arrows fired at them by attackers.

Made of wood, they were susceptible to fire. To counter an attack by fire, the hoarding was sometimes covered in wet animal skins, which were more fireproof. Being a temporary structure, it is believed that hoardings were disassembled and stored inside the castle during times of peace. Eventually, they would be replaced by crenellations and machicolations made of stone.

Hoardings were supported on a castle wall by putlog holes, wooden joists in the wall below, or permanent stone corbels.

Machicolations

An opening between supporting corbels of a battlement, through which defenders could drop stones, boiling water, etc., onto attackers at the base of the castle wall while providing protection.

Machicolations were more common in French than English castles, usually located above a barbican or gatehouse in front of a portcullis. They were later used as a decorative feature with spaces between the corbels but no openings from which to drop things.

Meurtrière / Murder Hole

A hole in the ceiling of a gatehouse or passageway in a castle, from which defenders could drop heavy objects on attackers trying to breach the entrance. Much like machicolations, which were gaps atop the outer wall of a castle, murder holes were similar but were located in the castle's interior after a portcullis gate to supplement the defenses of a gatehouse or barbican.

Objects dropped through a murder hole were usually heavy stone, scalding water, hot sand, and sometimes quick lime, burning oil. Quick lime was rarely used due to its cost. Scalding water and hot sand could penetrate an attacker's armor through the joints in the armor.

Palisade Wall

A row of high vertical standing tree trunks or wooden stakes forming a defensive wall around a castle. The stakes were sharpened to a point at the top. Palisade walls were located at the top of an earthwork in a ring castle or atop the motte and around the bailey of a motte and bailey castle. They provided extra defense for the people within the castle and a wall to keep livestock enclosed within the castle.

When William, Duke of Normandy, invaded England in 1066, he brought wooden stakes with him, stored in his longboats. Upon landing at Pevensey Bay, William quickly erected a wooden castle, using the stakes to form a palisade wall, creating Pevensey Castle, the first motte and bailey-style castle in England.

Because the fortifications were made of wood, they were vulnerable to fire. As castle construction evolved to improve defenses, wooden palisade walls were eventually replaced by stone. Sometimes, palisade walls were built as a temporary safeguard while stronger stone walls were constructed.

Portcullis

A heavy vertical closing latticed gate, usually made of wood, with iron tips at the bottom. These were placed at the entrance to a castle's gatehouse or barbican. The gate was set in grooves in the walls on either side of the gate and opened and closed using a chain and pulley mechanism in the room above the portcullis.

The lattice pattern of the gate allowed defenders to see people approaching the castle through the gate when closed and made the gate less vulnerable to fire than a solid wooden door.

Some castles, like Warwick Castle in England, had a portcullis on each end of the barbican, so attackers would have to break through two gates to get in. Moreover, attackers could be trapped in the area between both portcullises and attacked by burning wood, rocks, or heated sand being dropped on them through murder holes in the ceiling.

Postern Gate / Sally Port

A postern gate is a secondary gate in a castle's curtain wall. Often located in a concealed location, a postern allowed people to come and go from a castle without being noticed or using the main gatehouse. Since they were typically hidden and much smaller than a normal gatehouse entryway, they did not need to be defended as vigorously. The postern gate could be used as a sally port during a siege.

A sally port was a means to exit the castle to allow the defenders to counterattack the enemy outside. From the Latin word Salle, Sally was a military maneuver made by a defending force to harass attackers before retreating to their defenses. Port is from the Latin word Porta for door. Thus, a sally port was essentially a door in a castle that allowed troops to make sallies without compromising the defensive countermeasures of a castle.

Some postern gates were simply a second exit in a castle, on the opposite side, to make getting in and out easier or closer to a water source like a river. Some sally ports did not exit through a postern gate or castle wall at all, like in Knaresborough Castle in North Yorkshire, whose sally port starts through a door in the floor of the courthouse inside the inner bailey and tunnels underground until it exits below the castle at the base of the cliff near the River Nidd.

Butter Barrel / Butter-Churn Tower

A Butter Barrel or Butter-Churn Tower was a type of two-part tower where the upper section had a smaller diameter than the lower section. This type of tower provides a fighting platform and wall walk at the point where the tower narrows, while the upper section continues higher as a raised observation point.

These towers became popular in Germany in the 14th century. They do not provide much difference regarding defense compared with other types of towers and may have been more symbolic than strategic. Burg Marksburg's tall and slender Tower Keep, or Roman style bergfried, is a fine example of a Butter-Churn Tower.

Glacis / Talus

An artificial sloping face at the base of a castle tower or wall to strengthen the building against undermining. These also help repel attacks as large stones could be dropped from the machicolations down the outer wall of the tower, which would hit the talus near the bottom of the tower and ricochet sideways into the attacking forces. They also prevented siege towers from getting any closer than the base of the talus.

With the introduction of gunpowder, taluses evolved and sometimes had dirt and rock make up the slope with a stone layer on top. This helped absorb the power of cannon balls shot near the base of the wall and deflect them away to help reduce their devastating impact.

Horseshoe Tower

Structures used along castle walls to provide more defense. The inside of a tower provided space for storage, bedrooms, staircases, and fighting platforms on the roof.

Rectangular towers were easy to build and provided lots of internal space but were vulnerable to siege weapons and undermining damage. Round towers provided better defense against siege weapons due to the curve of the tower wall but sacrificed internal space.

Horseshoe towers were the solution that incorporated the strengths of the rectangular and round towers. Horseshoe towers were rounded on the side that extended outwards from the castle wall, providing the curved wall for deflecting projectiles, and the back end of the tower facing the inside of the castle was square, allowing more internal space.

The Curfew Tower at Windsor Castle is a fine example of a horseshoe tower.

Peel Tower / Pele Tower / Tower House

Small fortified keeps or manor houses, mostly built along the English and Scottish borders. Tower Houses were also popular in Ireland. Unlike large castles, Peel Towers were primarily stand-alone, self-contained, single tower castles with no other walls or buildings around them, except sometimes a barmkin, a small courtyard surrounding the tower, defended by a perimeter wall.

Peel Towers provided defense against raids and served as watch towers where signals fires could be lit to warn of approaching danger. A fine example of a Peel Tower is Smailholm Tower in Scotland. It has a barmkin that surrounds an outer hall and kitchen block, and its rooftop has a watchman's seat and a recess in the wall for his lantern. On a clear day, it is said that from the roof of Smailholm Tower, you can see Bamburgh Castle in England, some 33 miles away.

Quatrefoil Tower

A rare style of tower of unusual design, built in a quatrefoil plan consisting of four overlapping circular lobes shaped like a four-leaf clover. An entrance is between two lobes, while defensive turrets fill the spaces between the other. It was believed the shape would improve flanking fire by making more ground visible from the summit of the keep and improve the defenses of towers by better-deflecting projectiles.

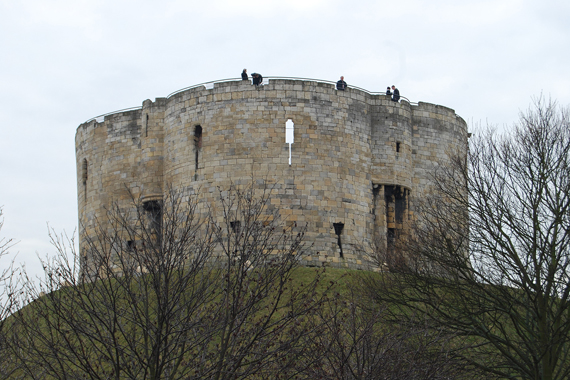

Clifford's Tower, the central keep at York Castle, is the only example of a quatrefoil castle in England, though the design can also be found at Château d'Étampes in France.

Rectangular Tower / Square Tower

Structures used along castle walls to provide more defense. The inside of a tower provided space for storage, bedrooms, staircases, and fighting platforms on the roof.

The advantages of rectangular or square towers were that they were easy to construct and provided the most usable internal space.

The disadvantages of rectangular towers were that the flat walls were more susceptible to damage from trebuchet attacks, as the large projectiles fired at them would make solid contact with the wall, causing considerable damage. The second vulnerability was that the tower's corners were vulnerable to undergmining. Attackers would tunnel under a castle's tower corners to cause the building to collapse when the ground underneath gave way.

Round Tower / Drum Tower

Structures used along castle walls to provide more defense. The inside of a tower provided space for storage, bedrooms, staircases, and fighting platforms on the roof.

Unlike rectangular towers, round towers were more resistant to siege weapons such as trebuchets as the curve of the tower provided a less flat surface, so projectiles would be deflected and cause less of an impact on the wall. They also had no corners to be exploited by undermining. The round shape had a drawback, as there was less space inside a round tower for rooms and storage. Round towers with a small diameter were often used as the outer walls of a spiral staircase.

You can sometimes identify these staircase towers from the outside as there will usually be arrow slits up the side of the tower in a diagonal pattern that follows the stairs as they lead up to let in light, placed often enough to see where you are stepping inside the staircase. A drum tower was a form of round tower, usually shorter and broader than a standard round tower, shaped like a drum as seen at the gatehouse at Skipton Castle.

Bailey / Ward

A leveled courtyard, typically enclosed by a castle's curtain wall. The outer portion of a motte and bailey castle. The courtyard provided lots of protected space behind the castle walls for things such as a blacksmith, stables, kitchens, wells, and chapels that were standalone buildings. If attackers breached the castle walls, they would find themselves in the open courtyard area and subject to arrows from defenders atop the walls, towers, or the keep.

Some motte and bailey-style castles had more than one bailey, such as Windsor and Arundel, with baileys on opposite sides of the motte, or inner and outer baileys when the baileys are nested inside the other. In times of war or attack, local villagers and livestock can be brought within the castle walls and reside in the bailey with enough food and supplies to hold out for months.

Blacksmith Forge

A place where black metal, or iron, is worked by a blacksmith by heating iron via a furnace and hammering it with hammers and an anvil to form needed items. Blacksmith forges were usually located within the castle walls as a separate building in the courtyard. Blacksmiths were crucial in a castle for making swords, armor, and horseshoes. But they also made nails, door hinges, and other metal items needed to maintain a castle.

Other smiths worked other types of metals, such as goldsmiths and silversmiths, but they specialized mainly in making jewelry and were less of a necessity in a castle.

Dungeon / Prison

A room or cell for holding prisoners. Most people picture a dark, dank room full of torture devices when they think of a castle dungeon. In reality, the idea of holding people prisoner was different in medieval times. Prisons were more of a short-term incarceration used to keep people until their trial could be held and just punishment was given, not as the punishment. At first, the castles were the prisons, where nobles were held for ransom and often given accommodation to match their status and allowed to roam freely about the castle.

But over time, some castles did start to use dedicated rooms as dungeons or prisons, usually underground in a basement, and those spaces were meant to be dark and uncomfortable. Some included torture devices such as the rack or a thing called the "Scavengers Daughter," which was a small metal cage suspended above the floor that would inhibit the capture from moving. These were meant to draw a confession from the person held captive to prove their guilt. In some castles, the prisons or cells were added much later, like at Richmond Castle or York Castle, and some were used until fairly recently at Lancaster Castle and Lincoln Castle.

Berkeley Castle's dungeon is famous for who it held, as Edward II was held captive there by his wife, Queen Isabella, until he was murdered there. The Tower of London served as a prison often. Sometimes, the prisoners would be given lavish living quarters and allowed guests, and sometimes, they were held in some cold tower out of sight. Many famous people have been held at the Tower: William Wallace, George Plantagenet, the Two Princes in the Tower (Edward and Richard), Anne Boleyn, Sir Walter Raleigh, Guy Fawkes, and Rudolph Hess. Among the last people to be held prisoner at the Tower of London were the Kray Twins, London gangsters in the 1950s and 60s. They were held at the Tower for a few days before being transferred elsewhere to await trial.

Keep / Donjon / Bergfried

A solid central stone tower, usually multiple stories tall and the last defensible stronghold within a castle, provides the highest level of protection. The keep was the most essential part of a castle and could be defended even after castle walls had been breached.

Keeps were originally called donjons, the French term for stronghold. The basement was sometimes used as a prison or dungeon, which became too easily confused with donjon, so the term keep was adopted. Original keeps in Norman motte and bailey-style castles were built of wood. Fire from arrows hastened the transition from wood to stone.

The first stone keeps, called shell keeps, comprised a simple stone wall that replaced the wooden palisade wall on the motte. These would evolve into the massive central towers we see today, though a few shell keeps still exist.

Keeps often contain a vaulted basement, hall, and other rooms such as bed chambers, kitchens, and a chapel. A keep could survive independently from the rest of the castle, apart from a freshwater source, unless the keep had an internal well or cistern.

In Germany, the central tower was called a bergfried, which they describe as a free-standing fighting tower. The bergfried was essentially the same as a keep, except it was for defense only and not for permanent habitation. Thus, it had few other rooms within it as within a keep.

Motte

Motte is the French version of the Latin word mota, meaning clump of turf. By the 12th century, the word motte was used to refer to the castle design itself in a Norman motte-and-bailey style castle, which is a castle with a wooden or stone fortification situated on a raised area of ground, or motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey. The Normans brought this castle style to England and Wales during the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and the style was later adopted in Denmark, Ireland, and Scotland in the 12th century.

It was common for motte-and-bailey style castles to have one motte and one bailey. Still, sometimes castles would have a single motte and two baileys, such as Windsor Castle or Arundel Castle, or two mottes and one bailey, such as Lincoln Castle.

The motte was made out of earth, usually built and not a natural hill, which was flat on top. Some were constructed over other artificial structures, such as Bronze Age barrows. Most early castles would have a wooden keep on top of the mound, replaced by stone keeps over time.

Mottes were encircled by a ditch surrounding the hill. Dirt excavated from the ditch was used to help build the motte. The soil used to form the motte made a difference as clay soils were sturdy and could be used to develop steeper mottes, whereas sandy soil required a more gentile incline. The higher the motte, the more protection it provided to the people inside the keep on top.

As castles evolved, some motte and bailey castles would build stone walls that would descend the whole slope of the motte, with the motte or hill hidden behind the stone wall. These were known as wing-walls.

Oubliette / Pit Prison

In French, the Oubliette, or place to be forgotten, is sometimes found in a castle's dungeon. As if being imprisoned in the dungeon was not bad enough, being sent to the Oubliette was horrible and usually spelled the end.

An Oubliette was a tiny space accessed from a trap door in the dungeon floor. Dark, damp, cold, and small, the person within could not stand up straight or lay down, causing muscles to lock up over time. As the French translation suggests, prisoners were usually sent to the Oubliette and left there to be forgotten without food or water until they eventually starved to death.

Secret Passages / Secret Chambers / Priest Holes

Many castles contained secret passages or rooms, which provided places for people to escape or hide in times of attack as a last defense if the castle walls and doors were breached.

Secret passages were usually located in a wall's thickness and accessed through a hidden entry like a doorway behind a wooden wall panel. The paths led to another area outside the castle, like a sally port exit in a curtain wall. At Château d'Amboise, secret passages lead under the castle to Clos Lucé, a house in town where Leonardo da Vinci lived. This allowed King Francis I to visit Leonardo without being seen walking through town.

Secret Chambers were also accessed through a hidden entry, but there was no exit out of the castle; they were just private rooms where people could hide until help arrived or the danger disappeared. They were also used in peacetime as a place to escape for privacy from visitors or spy on visitors. Eilean Donan Castle in Scotland has a secret chamber next to the great hall, where the Laird could watch and listen to guests through spy holes hidden in the wall between the rooms. These chambers were also used to hide items of value.

Priest Holes were small hiding places within a castle wall or under a floor, often used by priests to hide during religious persecution. These were very cramped and meant for hiding for a short time.

Spiral Staircases

Spiral staircases were usually built inside castle towers. They were typically made of stone, narrow, and dark, with the only light coming from an occasional arrow slit on the outer wall. Sometimes, they had uneven steps, either worn down through time or uneven on purpose, so an enemy would have more difficulty climbing the staircase.

The most important aspect of a spiral staircase is that the steps rotate clockwise as you ascend. If a castle was attacked and the enemy made it in and forced the defenders into a building, they would retreat to the higher floors. They could use the spiral staircase to their advantage. Since most people were right-handed, as they fled up the stairs, they could still maneuver their swords, while an attacker below him on the staircase could not fully swing a sword without the sword clashing with the newel, the stone center support beam of the staircase.

Some castles, like those in France's Loire Valley, have spiral staircases that rotate counterclockwise, providing no added defense for those defending the castle. These staircases seem much grander and broader, so the newel probably would not have burdened an attacker's swing. Or those were built after gunpowder was introduced and muskets replaced swords.

Stables

Stables were essential in a castle courtyard as horses were required for knights, hunting parties, or travel. Horses were also needed for pulling carts and farming plows. Stables often included hay lofts and living spaces for the grooms. Some castles would have multiple stables, using one for residents' or visitors' horses and another for breeding stallions or foaling mares.

The castle Marshal was in charge of the castle stables, and any fighting force garrisoned at the castle. Grooms of the castle swept out the stables and took care of the castle's horses as well as the horses of any guests.

Taxus Baccata / European Yew Tree

A species of evergreen tree in the Taxaceae family, commonly found in Western Europe, Great Britain, and Ireland. The yew tree can still be found growing in some castle courtyards. It produces berries, but the berries and most parts of the tree are poisonous and produce toxins absorbed by breathing and through the skin.

So why would such a dangerous tree be found in a castle courtyard? The yew tree can live between 400-600 years. Yew is among the hardest softwoods, yet it has remarkable elasticity, making it ideal for making longbows. The heartwood, best for compression, is always on the inside of the bow, with the sapwood, for tension, on the outside.

Yew trees were traditionally planted in castle courtyards and churchyards throughout Britain and Ireland as a resource for bows. According to some accounts, Robert the Bruce inspected and cut some of the yew trees at Ardchattan Priory to make the longbows used at the Battle of Bannockburn.

Well

Built inside a castle's bailey to supply drinking water for the castle. Wells were often the most costly and time-consuming element to build in a castle due to the depths they would have to be dug to reach a clean underground water source, sometimes taking decades to complete. The deepest castle well in England is located at Beeston Castle, whose well is 113 meters deep.

During a siege, the well provided a protected water source for people inside the castle. Water wells located outside a castle were often poisoned in times of siege to hasten a castle's surrender. If a castle had a protected water source inside its walls, they could continue to resist surrendering to a siege as long as their food sources held.

Bastion / Bulwark

A structure protruding from a castle wall, usually angular in shape and positioned at the corners. Bastions provided extra protection against cannon fire and became popular from the 16th to 19th centuries. Bastions were different from medieval towers as they were usually the same height as the adjacent curtain wall and covered a larger area than most towers, allowing space for cannons to be mounted atop them and crews to operate the guns. Bastions were also backed with solid earth to help absorb cannon fire, unlike hollow towers that contained rooms or staircases within.

Gun Loop / Gun Hole

After Gunpowder came to be, the concept of a gun loop began by altering an arrow loop to include a larger circular openings, or cannoniers, at the bottom of an arrow slit or round openings beside the arrow slits, which allowed small cannons to fire cannon balls at attackers.

Sometimes, gun holes would be in locations on their own, independent from arrow loops, at the base of a castle wall.

Ravelin / Demilune

A triangular detached outwork or fortification in front of a castle which provides extra protection for the castle by absorbing the impact of cannonballs. The walls would be backed by solid earth, providing the outer wall more support against the cannon fire. The triangular angle of the ravelin deflected the fire to the left or right and divided an attacking army. Ravelins were usually lower to the ground than the castle walls behind them to not impede the view of the surrounding area from the castle walls. The top of a ravelin was usually flat and used as a gun platform for cannons defending the castle, detached from the connected ring of walls and corner fortifications or bastions that make up the main outer perimeter of the fort.

Ravelins were the outermost part of the bastion fortification system and became a typical design in forts and barracks built in later centuries, including Forty McHenry in Maryland. You can see a ravelin in front of the main entrance to the fort in the bottom left corner of the picture.

Ashlar Stone / Dressing Stone

Finely cut stones, usually square or rectangular. The smooth surface of the outer layer of a castle wall. Ashlar stones are precisely cut on all faces, providing thin joints between blocks. The ashlar stone gave a castle wall a finished look, but the smooth surface also made it difficult for an intruder to climb, as the even surface provided very little to grip onto the wall. The space between a wall's inner and outer ashlar stone surfaces would be filled with unfinished stone, rocks, and rubble. Some castle walls could be 10 feet thick or broader, but only the outer surfaces have the ashlar stone.

As castles were abandoned and fell into ruin, people from nearby villages would sometimes remove the ashlar stone layer of a castle wall and reuse those bricks in churches or houses built in the town, as at Rhuddlan Castle in Wales. You can see the ashlar stone is missing from the bottom ten feet of the wall, exposing the rough rubble layer of the wall.

Dressing stones were also a form of ashlar stone, usually more prominent than the other ashlar stonework on a wall. They are used around doorways or window frames to provide more support for the window or door and decorative purposes, much like quoins at the corner of a castle wall.

Bakehouse / Brewhouse

Besides the kitchen for cooking and preparing food, most castles had other specialty rooms for preparing or storing food and drink. A bakehouse was used to prepare and bake fresh bread for everyone living within the castle. But man cannot live by bread alone. Some castles also had a brewhouse. Beer and ale were popular, but in the medieval period, it was safer to drink than water as brewing also sterilized the water, removing much of the pollutants. Beer was so popular that an “Ale Wife” would have been in charge of the castle brewery.

Bossed Stone

Stones that are intentionally left rough on the outward-facing side of a castle wall. This was believed to save money as it would have been a less expensive wall since it would not require a stone mason to smooth the edge. But thanks to texts on catapults, we now know stone bossing was done to strengthen a wall against heavy shots as the projectile would disperse its energy when striking an uneven surface.

Bower

The lady's withdrawing room. It was used as a bedroom suite by the lady of the castle where she could retire from the lord and uphold her privacy.

Buttery

A room in a castle, usually located near the Great Hall, where beer or wine was served. The room's name comes from the beer butts or barrels stored there. The person responsible for serving beer was the yeoman of the buttery. The buttery often had a staircase to cellars below that stored beer or wine. Wine cellars were more prestigious, with wine being more valuable than beer, and thus were controlled by a yeoman of the cellar and more ornately decorated.

Chapel

Religion was significant in medieval times. Christianity dominated all aspects of life, and almost all castles had a chapel in some form or another. Some were separate elaborate buildings, such as St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, while smaller castles may have just had a room with an altar. Some had multiple chapels, with a private chapel for the lord of the castle and a larger one for everyone else. Prayer in chapels was a daily event.

A chapel was believed to protect the part of the castle where they were located, so they were often located near or above the gatehouse. No one would dare attack such a holy place. In Europe, it was believed that nothing should be above God, so castle chapels were always on an upper floor or protruded from the side of a building, so no rooms were above the chapel. At the Marksburg in Germany, the chapel was located on the most vulnerable side of the castle to attack, where the walls were also the thinnest. God, its builders reasoned, would protect his holy sanctuary, so more robust defenses were unnecessary. Incidentally, the Marksburg is the only Middle Rhine castle never destroyed.

A permanent chaplain for the lord and his family's private use came along with the chapel. The chaplain presided over daily religious services but was also responsible for teaching the children of the castle because priests and monks usually had a better education than everyone else at that time. The chaplains also did most of the writing at the castle regarding correspondence for the castle lord.

Dovecote / Dovecot / Doocot

A structure for housing pigeons or doves. Dovecotes could be free-standing buildings in the bailey of a castle or built into the end of a house or barn. They contained pigeonholes along the interior walls for the birds to nest. Having a dovecote was quite a status symbol, and it was usually limited to nobility and closely regulated by law as to who could have one. Nobles who had this privilege were known as Droit de Colombier. Dovecotes were popular in Ireland, Scotland, and Northern England.

Dovecotes were important in castles as the eggs produced and the birds themselves were a source of food during cold winter months when other food sources were a bit scarce. The bird's excrement was used to fertilize crops, tan leather, and make gunpowder.

Drawing Room / Withdrawing Room

A drawing room was used for entertaining guests in a castle, more intimate than the great hall, like a living room today. It is derived from the term “withdrawing room,” where the castle lord could withdraw for more privacy. It was usually located off the solar or great chamber.

Garderobe / Dansker

The common term for a medieval castle toilet. It derives from the French Garde de robes, meaning robes protector. It was initially used to describe a small storeroom or closet that would be used to prevent clothes from getting soiled or used to store other possessions like jewels, spices, and money. The term became synonymous with a castle's privy or toilet.

A garderobe was usually a simple hole, or seat above a hole, that emptied to the outside of a castle into a pit latrine, moat, stream, or river, depending on the castle. These holes/seats were placed inside a small chamber to provide privacy, leading to the association with the term garderobe. Garderobes look a lot like a bretèche and are similar in construction, with garderobes being located over a water source or pit instead of over a doorway.

Clothes were sometimes hung near the garderobe as inhabitants of the castle believed that ammonia from the garderobe would protect clothes from moths or fleas. As indoor plumbing evolved, garderobes became obsolete.

A dansker, more common in Germany in the 13th and 14th centuries, was a type of garderobe tower linked to a castle over a bridge with a covered walkway and was usually found in castles that many people constantly occupied.

Garret

A habitable attic space, traditionally small and cramped, with sloped ceilings. Garrets were the most minor location in the castle. Garret is derived from the Old French word garir, meaning to provide or defend, with a military connotation of watchtower or garrison. They often served as a place for guards to be quartered in a castle.

Great Hall

The main room and the heart of the castle. The social gathering area to host guests and banquets. A great hall was usually rectangular and two to three times as long as it was wide. In medieval times, they were simply called a hall. One end of the hall would typically be raised with a high table where the King, laird, or guest of honor would be seated. Then, guests filled in the rest of the hall. The more important a guest was, the closer they sat to the front, near the guest of honor.

Due to the size of the hall, most would have an arched wooden hammer-beam roof, as the roof would need to be more robust to support the size of the room. These elaborate roofs look like the inside of a giant ship turned upside down. Halls were usually finely decorated and had ornate windows, large wooden tables, tapestries hanging on walls, etc., all meant to impress guests. The hall sometimes had a minstrels' gallery, a balcony above the entrance, where musicians could play music hidden from sight as seen in the picture of the King's Hall at Bamburgh Castle.

There are a lot of great halls that still exist today. The tables for hosting banquets are now gone in most cases, though the Guest Hall at Dover Castle is furnished as it would have looked during the Reign of Henry II. Some are impressive empty rooms where you can imagine how it would have looked when furnished. Some contain arms, armor, and other spoils of war. The most impressive great hall I have seen is at Warwick Castle, which includes over 1000 pieces of arms and armor, including artifacts from Oliver Cromwell and Bonnie Prince Charlie. St. George's Hall at Windsor Castle, rebuilt after the fire that occurred in 1992, is very impressive as well.

Ice House

As the name implies, an ice house was a special insulated place to store ice. They were found in basements, separate buildings, and woodland banks. During winter, when ponds and rivers froze, ice would be cut from the water source and taken to the ice house, where it was packed with insulation like sawdust or straw. There, it would stay frozen for months. Ice would primarily be used to keep perishable foods cold or to chill drinks. Ice houses often had a drain for melted ice to flow from the building.

Kitchen

Castle kitchens were similar to modern kitchens today, a place to cook and prepare food. The earliest kitchens had a hole in the center of the room's roof and a central fire underneath for cooking game and fish. The smoke from the fire would rise and escape through the hole in the ceiling. With the invention of the chimney, the fire moved from the center of the room to one wall. Leonardo da Vinci invented an automated system for a roasting spit, with a propeller in the chimney that turned the spit automatically. Before that, it was someone's job to rotate the roasting spit by hand. Some castle kitchens were large enough to roast up to three oxen at a time.

The kitchen was a hub of activity, with meals constantly being prepared. The kitchen was usually located apart from the living spaces and the hall. A common complaint in some castles was that the food arrived cold due to the distance from the kitchen. Some castle kitchens also had storehouses for storing food and ingredients and ice houses for keeping raw food cold.

Larder / Spence

The larder was a colder room in a castle, usually near the food preparation areas. They were used to store food before use and had cupboards, shelves, and even hooks from the ceiling to hang fresh game or meat. In Scotland, a larder was called a spence. In the Middle Ages, the person responsible for the larder, meat, and fish was called a larderer.

Oriel Window

A curved or polygonal window that projects from the wall of a building but does not reach the ground. Corbels or cantilevers supported Oriel windows, usually on an upper floor. The term Oriel derives from the Anglo-Norman oriel and Latin oriolum, meaning gallery or porch. Oriel windows provided more of a viewing range and were primarily decorative.

Pantry

The pantry was a side room from the kitchen where dishes, food, and bread were stored and served. Pantry is from the Old French term paneterie, which is from pain, the French form of the Latin term pan, for bread. In a castle, the pantry was where bread was prepared and kept. The person responsible for the pantry was called a pantler.

Quions

Large ashlar stone masonry blocks laid horizontally at the corners of a stone wall to add aesthetic detail to a corner, resulting in an alternating quoining pattern. Mostly, this was done merely for decorative purposes to imply strength, expense, and permanence, reinforcing the onlooker's sense of a castle's presence. The quoins were usually larger than the bricks or stones that made up the face of the wall.

Sometimes, the quoins are more than decorative and provide a load-bearing function for the wall or building. In this case, the stones would usually be laid in an alternating pattern of horizontal and vertical quoins.

Scullery

A room in the castle that was used for washing dishes and laundering clothes and was sometimes used as an overflow kitchen. Sculleries contained hot and cold sinks, shelves, plate racks, and a work table. Plates and dishes would be kept in the scullery until they were needed for meals.

For laundering clothes, the scullery would have a set pot for boiling water, a dolly tub for soaking clothes overnight, a wooden tub for scrubbing, and a mangle for squeezing water out of cloth.

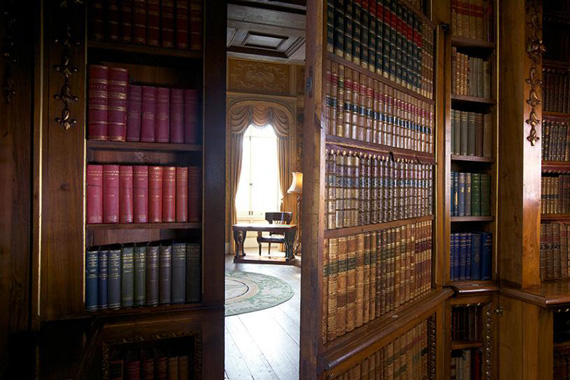

Solar / Great Chamber

A room in many manor houses and castles, mainly on an upper floor, used as the family's living space and sleeping quarters. Unlike the great hall, used for hosting guests and banquets, the solar was the private part of a castle. Generally smaller than the great hall, it was a room of comfort and status and often included a fireplace, tapestries, and decorative woodwork. It was the place for the family to retreat away from the noise of the day-to-day running of the castle. They were often called the Lords' Chamber or Great Chamber in a castle.

The solar was sometimes located in a separate tower from the great hall to provide more privacy.

Wardrobe

This room was where the clothes were kept. It was used as a small dressing room and, over time, was used to store valuables such as furs, coins, and jewelry.